Established 2023

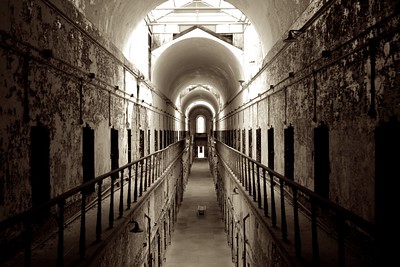

Growing Up Behind Walls Childhood at Eastern State Penitentiary

Monday, November 11, 2024

Olubukola Alliyu

Jimmie Double-O

Among the shadows of confinement at Eastern State Penitentiary, records reveal a surprising figure: a child known as 'Jimmie O O' (or 'Jimmy Double-O'). Mentioned in the prison publication The Umpire in 1916, Jimmie's presence adds an unexpected dimension to the institution's history. This essay explores Jimmie's life within the prison, offering a rare glimpse into how the experiences of one young resident intersect with the rigid structures of such an austere environment.

Jimmie O O, whose name appears frequently in The Umpire, was a child whose interactions within Eastern State hint at his impact on the prison's inhabitants. The Umpire doesn't go into details of his background, but his mention among adults who were incarcerated suggests that he may have been a source of joy or escape for the community. He appears less as an inmate and more as a figure that many prisoners loved.

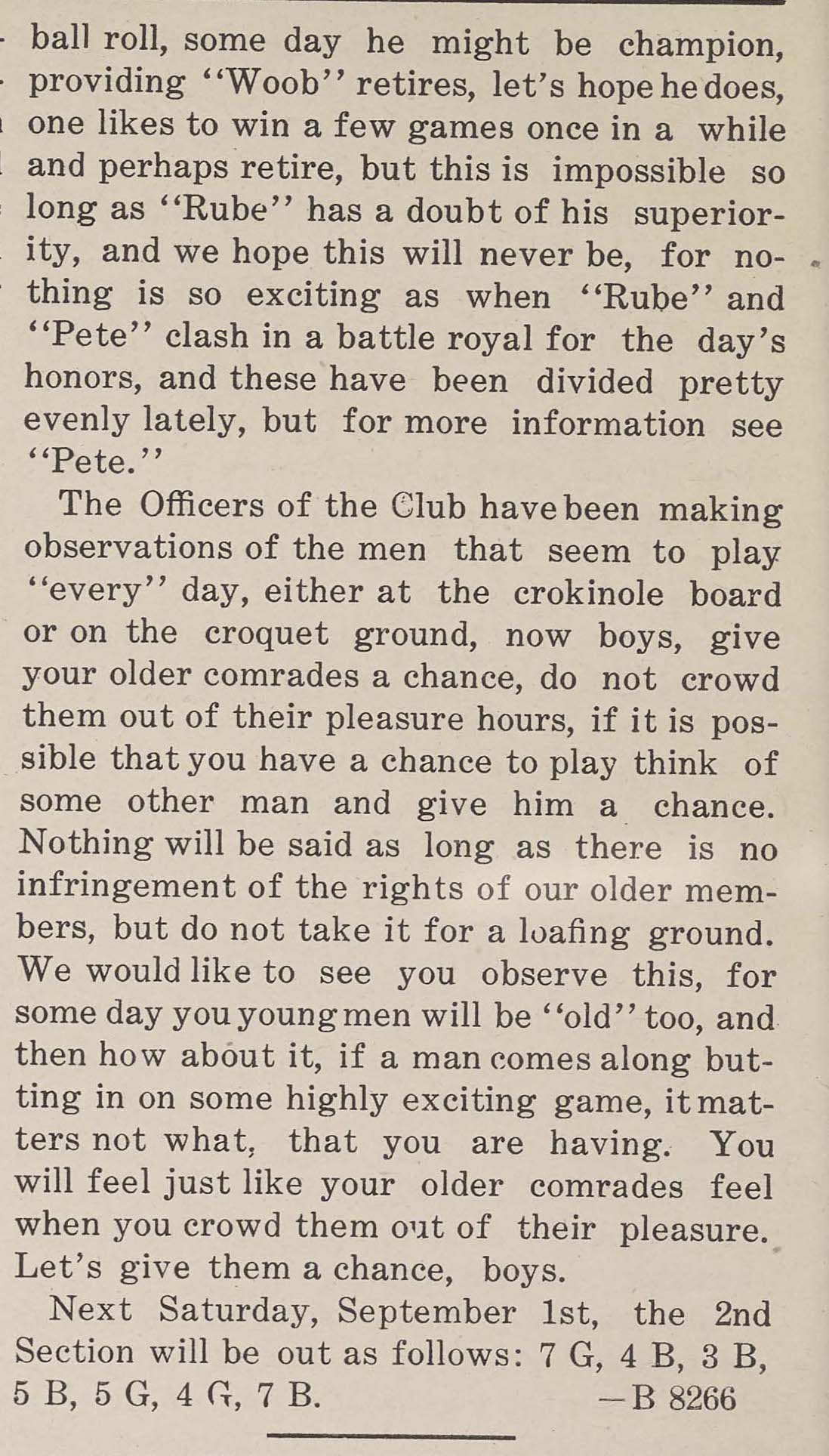

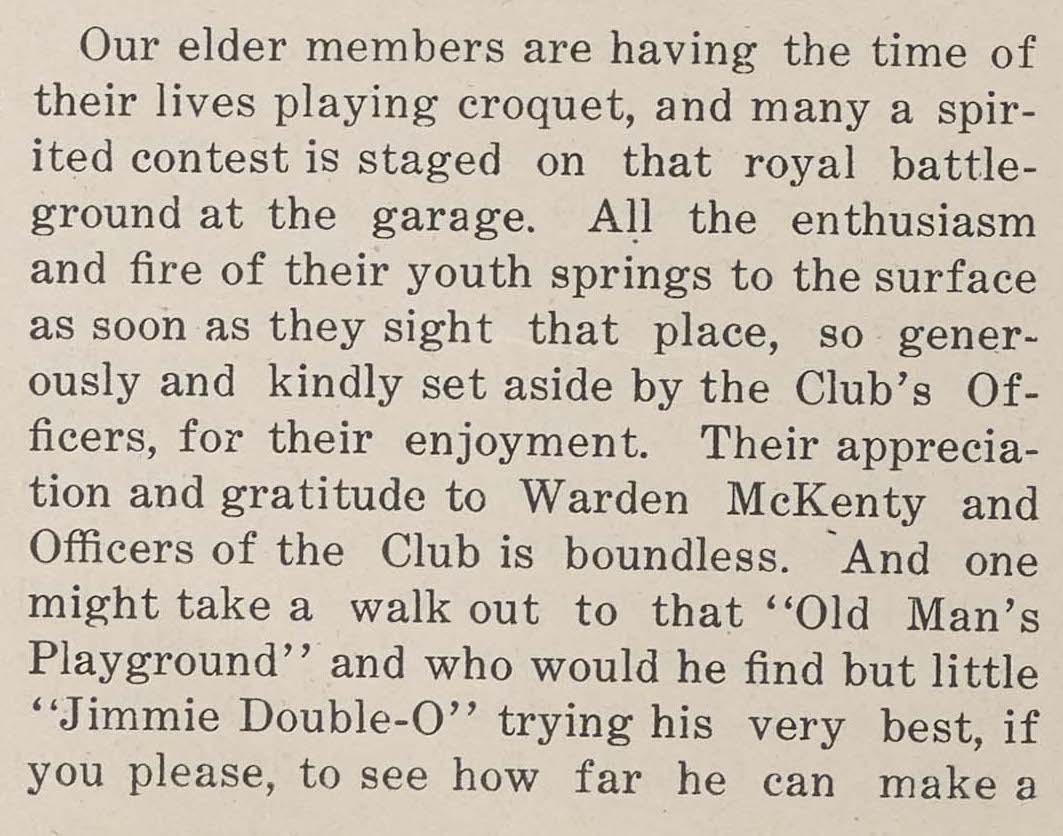

Issue of The Umpire, August 1st, 1917 – This prison publication often featured updates on Jimmie’s activities and interactions with inmates.

Jimmie O, born within the walls of Eastern State Penitentiary, became an unexpected source of joy and normalcy in an otherwise austere environment. At just one year old, he had already endeared himself to the inmates and staff, serving as a beloved figure who brought a touch of innocence to the prison yard. His presence offered glimpses of childhood that likely reminded many of their own children or siblings outside the prison walls.

"Who ever heard of a kid in a can before?"

The impact of his presence was profound and far-reaching. Men would stand in open-mouthed wonder at the sight of him, their amazement captured in the candid observation of one inmate who marveled, "Who ever heard of a kid in a can before?" This simple, unpolished expression revealed the extraordinary nature of having a child within the prison walls. From the highest-ranking officials like Warden McKenty to the fourteen hundred "cons" and countless visitors, Jimmie's presence touched everyone who encountered him, inspiring a universal affection that transcended the usual barriers of prison life.

For Jimmie, the prison community was his world, his normal. The care shown by inmates like "Happy," who acted as a careful nurse, and the collective effort to provide him with gifts and necessities, demonstrate how the prison population came together to create a semblance of family for the child. The community fully embraced Jimmie, outfitting him with his own uniform cap and treating him as a true part of their unusual family.

Jimmie's "strutting" around the yard and attempts to roll a ball in the "Old Man's Playground" highlight how he actively engaged with his surroundings, oblivious to the stark contrast between his innocence and the harsh realities of incarceration. His presence served as a bridge between the confined world of the prison and the outside, offering inmates a chance to express nurturing instincts and experience moments of lightheartedness.

Jimmie's presence offered inmates moments of lightheartedness and the chance to express nurturing instincts, bridging the harsh realities of incarceration with glimpses of humanity and connection. His story sheds light on the inherent humanity that exists even within confined walls, giving us a nuanced perspective on prison life without diminishing the gravity of its circumstances.

The story of Jimmie O O, preserved in the pages of The Umpire, reminds us that even in the harshest settings, moments of innocence and connection can emerge, offering a rare glimpse of humanity behind the prison walls.

Mothers, Toddlers, and the Incarceration Narrative

The presence of toddlers like Jimmie O. O. at Eastern State Penitentiary offers a stark reminder of how incarceration can ripple far beyond the individual, profoundly affecting families. Their presence underscores the intersection of women’s imprisonment and childcare, revealing that incarcerated mothers had no choice but to bring their children into a space inherently designed for punishment and correction. This tells us something significant about women’s roles in the prison system: they are both subjects of incarceration and caretakers, caught in a system that often disregards the unique needs of women as mothers.

While women did not write The Umpire, their children nonetheless appeared in its pages, raising questions about how incarcerated men chose to represent them. The language used to describe children in the publication often oscillates between sentimentality and a sense of novelty, depicting these toddlers as “mascots” or “little inmates.” Such descriptions, while affectionate on the surface, reinforce the idea of children as anomalies within the prison—a curiosity rather than a serious consideration. The men’s decision to write about the children may reflect their own longing for family connections or their attempt to humanize the prison environment, yet it also highlights a gendered silence around the women themselves. By focusing on the children, the narrative sidesteps the conditions and experiences of the mothers who were raising these children in confinement.

This portrayal also sheds light on the broader history of children in prisons, a history marked by invisibility and erasure. Children like Jimmie O. O. were not just witnesses to their mothers' incarceration but were themselves enmeshed in the carceral system. The language used to describe them in The Umpire mirrors historical trends that frame children as passive extensions of their parents rather than individuals with distinct rights or needs. Such narratives downplay the systemic failures that lead to children living in prisons, instead framing their presence as incidental or quaint.

Ultimately, the story of toddlers like Jimmie O. O. reveals the uncomfortable truth that prisons were never designed with families in mind. Their presence within these walls underscores the systemic oversight of women’s roles as mothers and highlights how children have historically been collateral damage in the carceral system. This legacy calls for a more critical examination of how prisons impact families and a reimagining of justice systems that take into account the interconnectedness of those they incarcerate.

References

The Umpire, 157 (1918)

The Umpire, 128 (1917)

The Umpire, 124 (1917)

The Umpire, 142 (1917)

The Umpire, 012 (1918)

Made use of perplexity to help with grammar and the overall flow of the content

.jpg)