Established 2023

My (Great-)Uncle Walter

Monday, November 11, 2024

Sophie Gala

My (Great-)Uncle Walter

Walter Gala was a Philadelphia native who became a practiced nurse during his incarceration at Eastern State Penitentiary between 1949 and 1967 for the first-degree murder of his wife, 22-year old Ruth Gala. He appears in the public record through census records listing basic information, news coverage over the murder that led to his incarceration and his eventual commutation, and features in Eastern State’s prison newspaper, the Eastern Echo. Details from how he appears in the written record, considered within the context of the institutions and relationships that shaped him, offer greater clarity on the significance of incarceration within his life’s trajectory. Overall, the constraints of imprisonment in combination with Walter’s choices while incarcerated led to years in the otherwise inaccessible field of nursing, shifts in family relationships marked by absence and an interruption of patterns of violence, and the formation of a positive reputation which influenced his ultimate commutation. Further, the written sources he appears in possess lenses and biases that further illuminate major themes in his life: limited consideration of his history of interpersonal harm, strained familial connection, and belief in the potential of prisoners for rehabilitation. He is also my great-uncle, and consideration of my connection to a historic institution dedicated to incarceration through his imprisonment has led to greater reflection on the presence of the carceral system in present-day Philadelphia, as well as the value of work to weaken its reach.

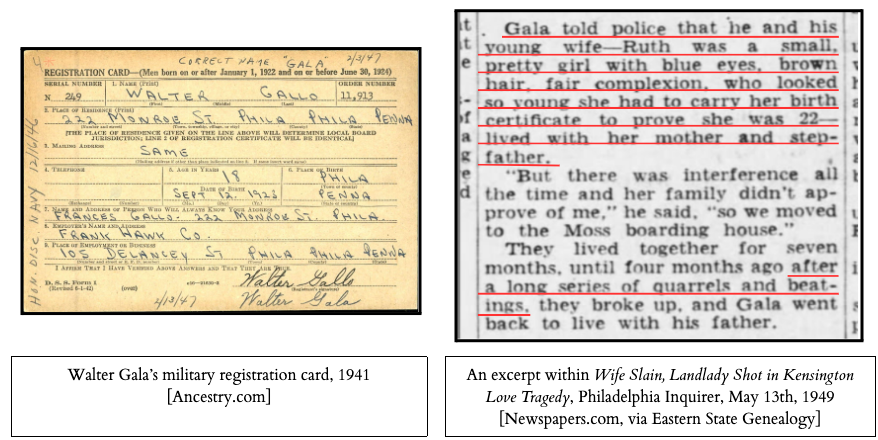

Walter was raised in a large Polish-American family, second-youngest of eight siblings according to 1940 census records. The Galas emigrated from Poland around 1900, part of the thousands of working-class eastern European immigrants who settled in neighborhoods with industrial jobs, including North Philadelphia and Kensington. His father Casimir worked as a boiler operator at the city's docks, as would his son and grandson, and the children were enrolled in the local Catholic school. Semi-skilled, routine work in Philadelphia’s industrial plants provided working-class stability to the neighborhood, much of which had limited formal education. At age nineteen Walter joined the Navy, starting a tradition of enlistment followed by at least his brother and two nephews, and served during World War II. He returned to his neighborhood after an honorable discharge in December of 1946, and married Ruth E. Hopkins on June 2nd, 1947, who was then no older than twenty-one. Ruth is only captured in census records once, in 1940, at which time she appears to have been staying with extended family members in the same neighborhood vicinity as the Gala family. Although she was thirteen, her highest education is recorded as the fifth grade.

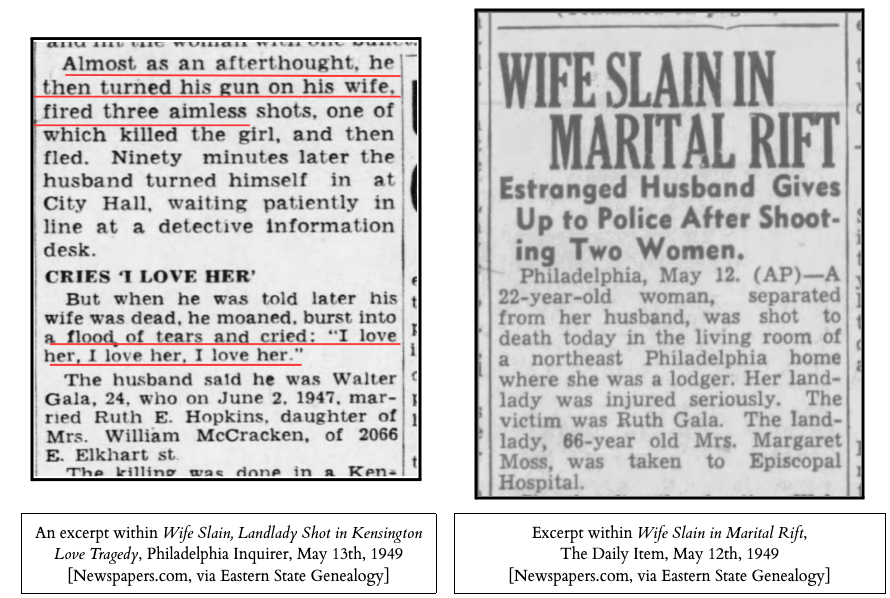

The limited news coverage which provides the only available accounts of Ruth’s murder confirm a violent marital environment later substantiated by a probation sentence, but reporters are hesitant to paint a particular picture of the culprit. The May 1949 Philadelphia Inquirer article details Gala’s 1942 conviction for a stabbing, plus his arrest in April of that year for severe domestic violence, resulting in a probation sentence that ended just ten days before the murder took place. The article explains a pattern of “quarrels and beatings” had started four months before, plus Ruth’s choice to file for divorce after her husband was set free on probation. However, the paper doesn’t cast Walter in a particularly harsh light, mentioning “aimless” shots, cries of love for his late wife when informed of her death, and reflections on loading his gun: “I didn’t do it with any intention of killing anyone”. Another local newspaper, the Daily Item, recounts the events without consideration of the crime’s cause. Despite identifying a history of interpersonal violence and an immediate motive, the most detailed public records of Ruth’s life did not come to her defense. The only photo of her to appear in available press coverage of her murder features a caption which ends with a description of her husband: “Gala is a Navy veteran”.

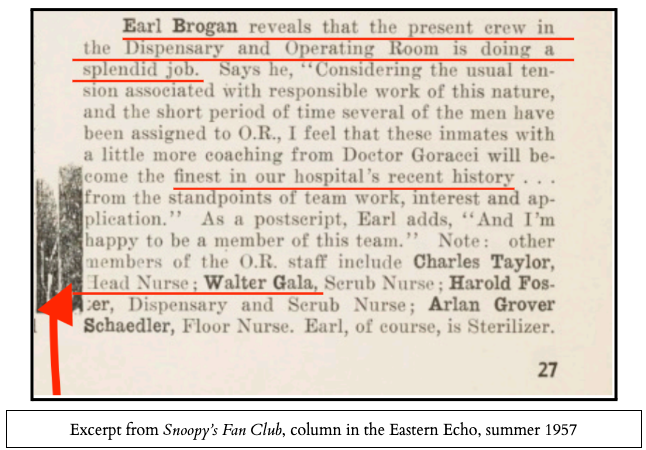

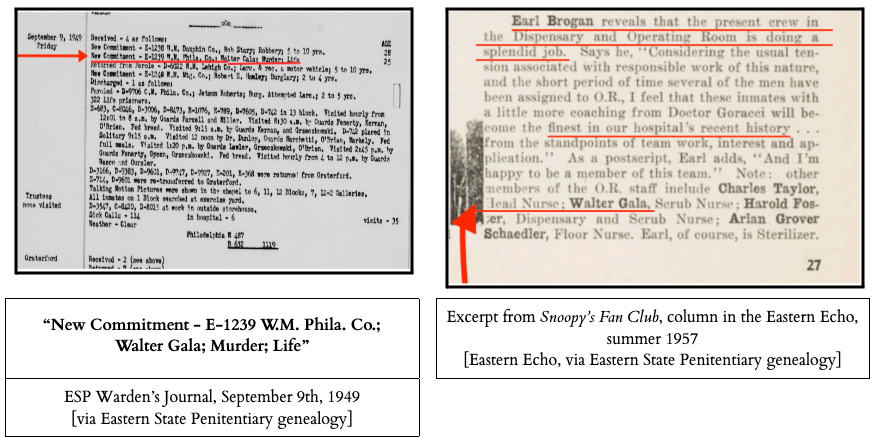

Walter entered Eastern State on September 9th, 1949, during a period in which the prison had shifted towards a variation of its grounding “rehabilitation” model that granted more autonomy to those incarcerated there. Founded in the early 1800s on the belief that extended, absolute solitary confinement would inspire “penitence,” the Penitentiary gradually abandoned total isolation and expanded to accommodate an increasing population. By the mid-1900s, some of those incarcerated at Eastern State held positions of specialized employment, paid below-poverty wages to subsidize industry and help run the prison. Although the 1940 census records that he did not progress past ninth grade, Walter began work as a nurse in 1949. By 1957 he had risen to the position of Head Nurse, which he presumably retained, based on later accounts of his work, for the remaining ten years of his imprisonment. His work leading a team in the operating room is praised by a fellow worker in a 1957 article of the Eastern Echo, the prison’s newspaper printed for internal consumption. While institutional records from the prison confine mention of him to his prisoner number, even a limited account of his work through the lens of other incarcerated workers sheds greater light on his character through how he chose to spend his time while in prison.

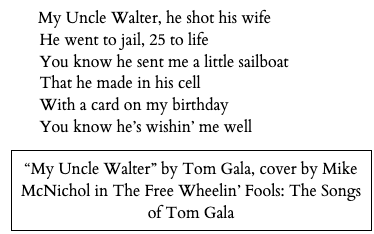

Despite spending nearly two decades incarcerated, Walter’s life did not exist alone within the vacuum of the penitentiary. Rather, his familial relationships were shaped by his physical absence. For example, his young nieces and nephews knew him only through limited mail sent on special occasions, like a letter sent at some point in the 1950s to his nephew Tom with a warning “not to end up like me”. Born in 1942, Tom Gala’s ballad “My Uncle Walter” recounts the relationship formed by interaction with the prison system, one fundamentally centered on crime and isolation.

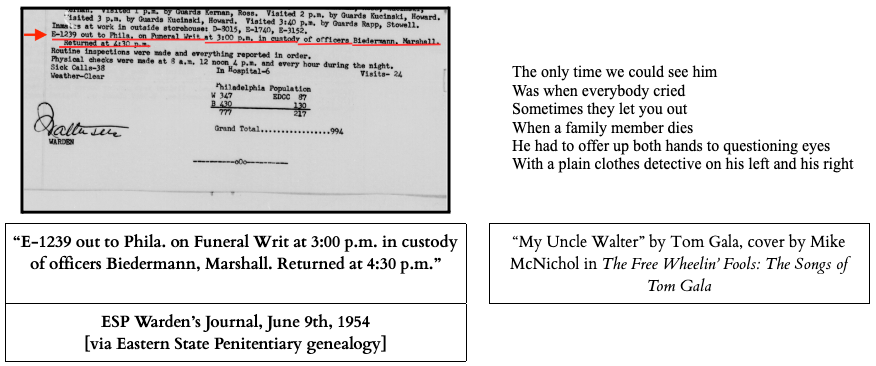

However, also present in this account is evidence of effort on Walter’s part to not fracture family relationships, but rather to connect emotionally with his family despite his circumstances. These contrasting forces can be seen again in 1954, when Walter’s younger brother Stephen passed away unexpectedly, and he was permitted to leave the prison for 90 minutes with guards to attend his funeral. In Tom Gala’s recollection decades later, his uncle’s rare presence is framed by the presence of Penitentiary guards, exactly matching the warden’s journal entry permitting the brief leave.

His incarceration also removed the possibility of continuing the cycle of interpersonal violence that had impacted Walter’s community for years before his incarceration. In this way, blank spaces in the historical record created by his imprisonment could also represent increased safety and autonomy for the family members he left on the outside.

Walter’s work as a nurse in Eastern State’s operating room stands out as a particularly valuable career opportunity when viewed in comparison to the livelihoods of his family members. In 1950, a year after Walter had started working as a nurse, census records substantiate that his father was a boiler operator and one brother a hospital orderly, while another brother and his wife worked in a cotton manufacturing factory and for a paper box company, respectively. Although he was one of the most educated in his family, with a ninth grade education he would not have been able to enter one of the hospital or college degree programs needed to work as a nurse in a standard facility. Although opportunities like the G.I. bill expanded college access and mortgage attainability after World War II, much of Walter’s family lacked the requisite education or financial stability to capitalize on them

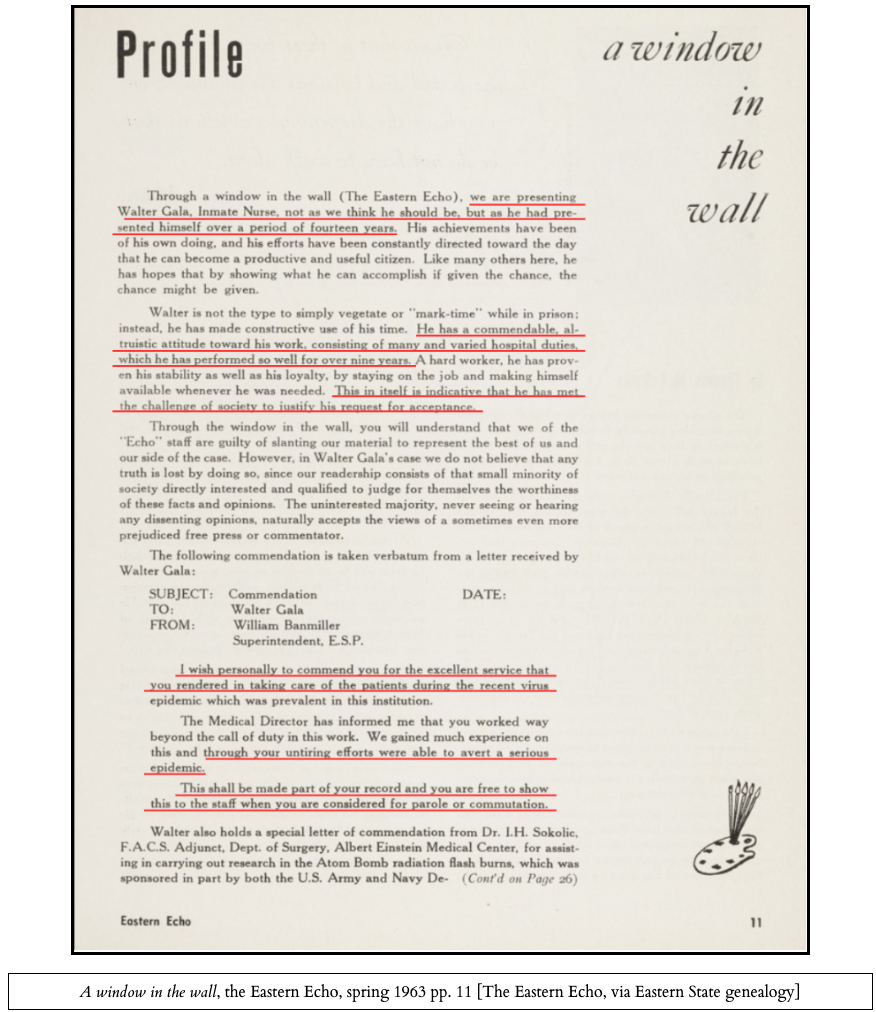

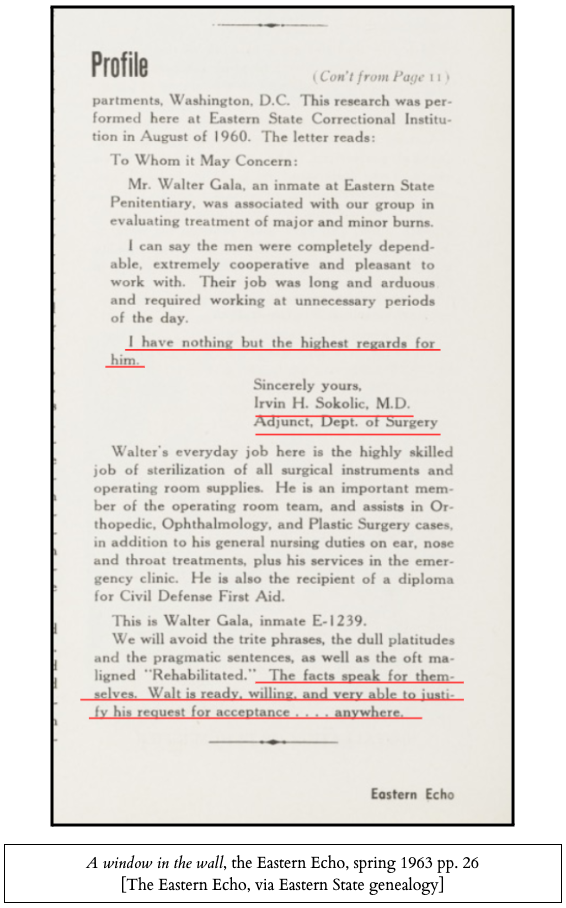

His position as a nurse while at Eastern State not only structured Walter’s working life while incarcerated, but also shaped positive perceptions of his character. This trend is demonstrated by an article written about Walter in the Eastern Echo, a quarterly periodical produced by and for those incarcerated in the prison. The profile was a part of the series “a window in the wall,” and aimed to describe its subject “not as we think he should be, but as he had presented himself over a period of fourteen years”. The author praised Walter’s work ethic as a member of the operating room team, writing that he “has a commendable, altruistic attitude toward his work, consisting of varied hospital duties, which he has performed so well for over nine years”. The emphasis of the piece is on commendation by the prison’s superintendent and a doctor in the Department of Surgery, the latter of which says he has “nothing but the highest regards for him”. The superintendent’s writing begins “I wish to personally commend you,” citing that Walter’s work during a recent virus outbreak allowed the prison to “avert a serious epidemic”.

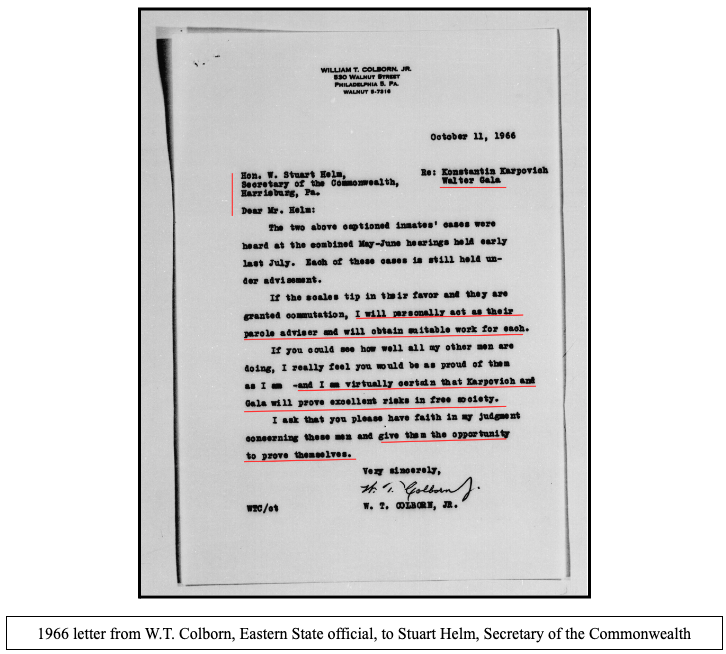

Positive accounts around Walter’s character, based on his work as a nurse, affirmed his character in the context of potential for early release. The author of the Eastern Echo article connects Walter’s work as a nurse with his readiness for reintegration into the civilian population, concluding: “The facts speak for themselves. Walt is ready, willing, and very able to justify his request for acceptance….anywhere”. Further, the Superintendent confirms that his commendation “shall be made part of your record and you are free to show this to the staff when you are considered for parole or commutation”. When he was in the process of applying for commutation of his sentence, the reputation Walter had cultivated while at Eastern State played an important role in garnering support from its staff. For example, in 1966, a prison official named W.T. Colborn wrote about Walter’s readiness for release in a letter addressed to the secretary of the commonwealth: “...I am virtually certain that…Gala will prove [an] excellent risk in a free society. I ask that you please have faith in my judgment concerning these men and give them the opportunity to prove themselves”. Walter’s dedicated work as a nurse within the constrained prison environment led those around him at Eastern State to present him in a positive light in written accounts, eventually his status as a prisoner by enabling a strong application for commutation.

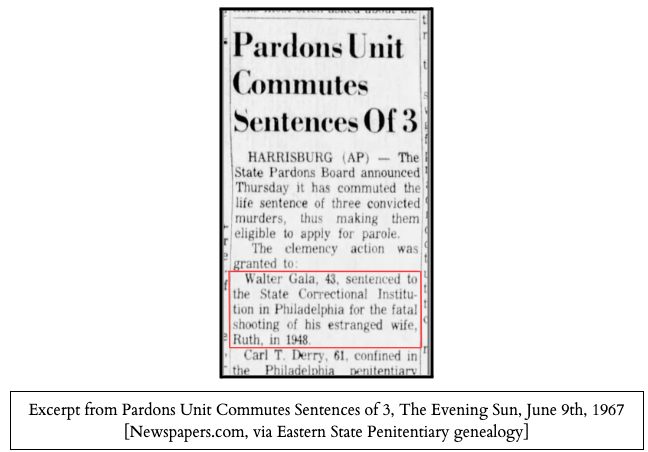

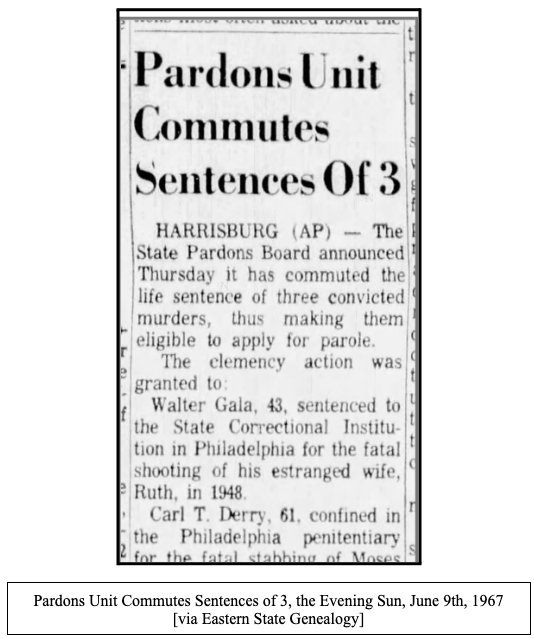

On Thursday June 8th, 1967, Walter Gala’s sentence was commuted by the State Pardons Board, after having served nearly eighteen years at Eastern State. He had worked in the prison’s operating room and medical facilities for the entirety of his sentence, including as a head nurse for ten years. He was 43; his late wife Ruth likely would have been 41.

Written records around Walter’s initial crimes and imprisonment help to clarify the role long-term incarceration played in his life. Imprisonment was both a source of isolation and an opportunity to gradually change perceptions of his character through dedicated, productive work. Gaps in the record create holes, producing questions: how did Walter consider his time at Eastern State? How did his community and family’s lives change because of the murder of his wife? What information could have been gathered about Ruth’s life if she had survived further into adulthood? However, the perspectives of source authors address major themes around how he was viewed by the people around him. Authors of media coverage of his crime were hesitant to draw harsh conclusions about him, a song by a family member speaks to gestures of care within a relationship defined by absence, and prison workers and staff advocated that he was deserving of early release.

————————————————————————————

Having an extended family member who was incarcerated at Eastern State serves as a grounding reminder to me of the enormous reach of the prison system, a concept that is reinforced by my regular volunteering with a local organization dedicated to community legal process support. When I have visited Eastern State in the past, I am always struck by the sense that the suffering inherent to imprisonment experienced by prisoners including my great-uncle Walter extends into the present, that the impacts of isolation and constraint are not circumscribed by the historical record. Although the vast majority of those incarcerated at the penitentiary are no longer alive or imprisoned, the legacy of their incarceration is felt by their living relatives and the contemporary iterations of their communities. To me, the central placement of the penitentiary along a popular commercial street leading into center city is symbolic of the role prisons have had in altering the lives of Philadelphians across generations, although most are far less visible.

I see this impact most clearly through taking weekly meeting notes and completing outreach for the West Philly Participatory Defense Hub, a community group that provides advice, support, and resources to fellow Philadelphians impacted by a criminal case. Hub members connect family members of incarcerated people with contacts at local justice and legal assistance organizations, show up in the courtroom, explain steps of given types of court dates, provide informal advice, and more. By participating in conversations in which individuals share their direct experience, I’m able to learn more about the many interactions and injustices of the carceral system. I aim to increase the capacity of the Hub to enable community members to access opportunities like specialized, productive work and community-based restoration- facets of life respectively enabled and constrained by incarceration for Walter Gala- while minimizing interaction with the prison system. For me, that is his clearest legacy- inspiration to work in circumstances defined by the carceral state to produce healing.

————————————————————————————

Thank you to Erica Harman, Archives and Records Manager at Eastern State Penitentiary, for locating key sources for this project.