Established 2023

The Rev. Joseph Welch, Moral Instructor

Monday, November 11, 2024

Justin Seward

The Rev. Joseph Welch, Moral Instructor

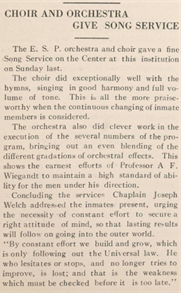

The chaplain of ESP was the Rev. Joseph Welch whose official title was “Moral Instructor” of the facility. Welch was responsible for not only the spiritual needs of the inmates, but also for the moral reformation of the incarcerated individuals in the prison. At this time, it was ESP’s mission to reform the incarcerated, and Welch was a critical component in this internal moral reformation. Welch would speak at services, Bible studies, and events about “inducing a higher ideal of life and a desire for moral betterment.”1 The Umpire repeatedly reported on Welch’s insistence on a moral life when he spoke at events:

Chaplain Joseph Welch addressed the inmates present, urging the necessity of constant effort to secure a right attitude of mind, so that lasting results will follow on going into the outer world. ‘By constant effort we build and grow, which is only following out the Universal law. He who hesitates or stops, and no longer tries to improve, is lost; and that is the weakness which must be checked before it is too late.’2

Welch served in the Union army as a chaplain throughout the American Civil War as an ordained Methodist Elder. Welch oversaw the religious services in ESP, including weekly or monthly Catholic, Episcopal, and Jewish services.3 His role was as much religious as it was institutional, and the emphasis on reforming the individual through confinement was accomplished through living a moral life—which is depicted as a Christian life in the Umpire and in Welch’s own writings—and a productive one with employment. Welch sought to instill discipline through religion to the prisoners of ESP, and the Umpire seemingly supports this aim:

There is much interest shown by Chaplain Welch in a Bible class organized among the members and presided over by him. The talks and instruction given on each Friday are beginning to show results and many members are learning that the Bible is a wonderful book and well worth the study.4

As a Methodist elder, Welch represents the largest religious movement at the time which is unique as a distinctly American Protestant denominational affiliation. The emphasis on reform in prisons is highly related to Christian and specifically Protestant ideals, as Max Weber would suggest. It would not be a mistake that the “Moral Instructor” of the prison was a Methodist, especially as Methodists and other mainline Protestant groups became enamored with the social gospel—the public theology which suggests Christians should work to improve society through legal and personal reform.

Welch describes his day-to-day actions in a journal article published by the Pennsylvania Prison Society. Welch writes that between him and his assistant, the Rev. H. Cresson McHenry, they attend to all of the over 1,200 prisoners in ESP. Welch claims that in one year he worked 352 days of the year and met with prisoners over 4,000 times in their cells or at the cell doors.5 Welch writes,

No person leaves that prison without my visiting him several times previous to discharge, ascertaining their needs, and providing them with suitable clothes, that they may make a respectable appearance in looking for work; pleading, too, with them to give up all their sinful ways, and give their hearts to the Lord—for there are no joys comparable to the “Joys of God’s Salvation.”6

Welch’s whole existence is devoted to reforming prisoners to make them more moral. Morality in this state-sanctioned institution is being defined as being Christian and able to work. Welch makes considerable personal expense to help prisoners when they are released, meaning he is personally committed to this endeavor in addition to being an agent of the state. He accounts that in one year he purchased 164 train tickets for prisoners upon their release at the cost of $377.50. He also notes that he helps prisoners find jobs which is something deeply connected with living a moral, Christian life.7

He describes handing out calendars at the new year, praying that they would be the means “of reaching many souls and bringing them to Christ,” with Christian sayings like:

O! the things WE call the LITTLE sins,

Are hateful in GOD’S SIGHT;

HE counts NO SIN a LITTLE sin,

Nor calls a WRONG DEED—Right!BEGIN thou first with LITTLE THINGS,

The smallest SIN AVOID and HATE;

Obedience to LOVE adds wings,

And LITTLE faith will grow to GREAT.

The statutes of the LORD are RIGHT—!

REJOICING the HEART.

(Psalm xix: 8)8

He also provides some successful cases of released prisoners succeeding post-incarceration. He describes them by noting three things: whether they are Christian and have joined a church, whether they have a job, and whether they have gotten married and started a family. He mentions several men who joined either the Methodist or Episcopal Churches with jobs as bakers, tradesman, or factory workers and accounts of marriage and new babies.9

Welch was depicted in the Umpire as being much beloved, although they likely would not have published any negative sentiment about him even if some harbored it. In one instance, in 1918, he was presented with a “silver loving cup” by “almost every church in the city” to celebrate “his efforts to cooperate with them in looking after the spiritual needs of the prisoners in that institution.” At the time of this award, Welch had just turned 82 years old and had served as chaplain of ESP for 27 years.10

In the beginning of 1920, after 28 years as chaplain, he was suddenly dismissed from his position. The governor had started an investigation into him and Prison Inspector William A. Dunlap for conspiring against Warden Robert McKenty. In what turns out to be the very last letter Welch ever writes, he responds to the Rev. Thomas Latimer, “I had no idea of being involved in any controversy about the prison until the Governor announced his intention to make an investigation and that it was ‘a close corporation with a one-man power’—those were his words.” In response to Latimer writing to Welch that he was on his side, Welch wrote, “I appreciate [the] sympathy. But you are off about ‘my side.’ I have no side. It is God’s or nothing.” Welch concluded his last letter with the statement: “I am satisfied; my case is with God, not the Governor.” Only four days after his abrupt dismissal, Welch died at the age of 83.11

The prisoners of ESP were distraught by the investigation into him, offering to write letters to the committee on his behalf. Upon his death and interment at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, ESP prisoners sent flowers and a letter “expressing the unanimous sentiment of all the inmates” of their regret over Welch’s passing.12

Welch’s dismissal and demise being so close together is curious, and the Philadelphia Inquirer addressed this by publishing the account of Joseph Welch’s son, B. Harvey Welch, who claimed his father’s health had been failing for years and that he had been “exceptionally cheerful of late and had accepted his discharge.” It remains interesting that as soon as Welch’s vocation and charge in life was over, he also passed.13

References

-

1579 “Episcopal Services and Baptism,” Umpire, June 21, 1916.

-

1581 “Choir and Orchestra Give Song Service,” Umpire, June 28, 1916.

-

“Prison Chaplain 28 Years; Ousted; Dies in 4 Days,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 19, 1920.

-

2856 “Honor Cub Notes,” Umpire, July 18, 1917.

-

Pennsylvania Prison Society, Journal of Prison Discipline and Philanthropy, vol. 40, 1901, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/56904/56904-h/56904-h.htm.

-

Pennsylvania Prison Society.

-

Pennsylvania Prison Society.

-

Pennsylvania Prison Society.

-

Pennsylvania Prison Society.

-

4437 “Penitentiary Chaplain Presented with Silver Loving Cup,” Umpire, December 4, 1918.

-

“Prison Chaplain 28 Years; Ousted; Dies in 4 Days.”

-

“Prison Chaplain 28 Years; Ousted; Dies in 4 Days”; “Bury Prison Chaplain,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 22, 1920.

-

“Prison Chaplain 28 Years; Ousted; Dies in 4 Days.”

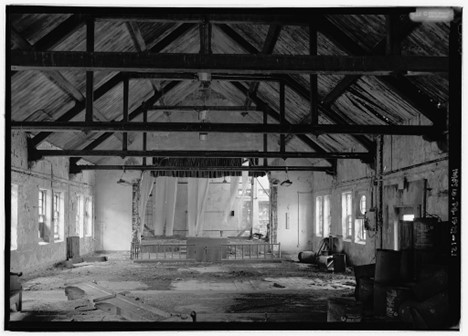

Image 2:

Boucher, Jack E. Interior View, Chapel in Industrial Building. 1998. Pennsylvania -- Philadelphia County -- Philadelphia. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/pa1207.photos.205973p/.

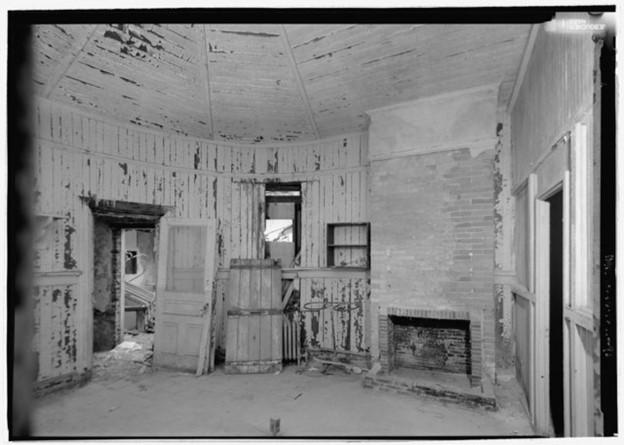

Image 3:

———. Interior View, Chaplain’s Office. HABS PA,51-PHILA,354-. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.pa1207.photos.

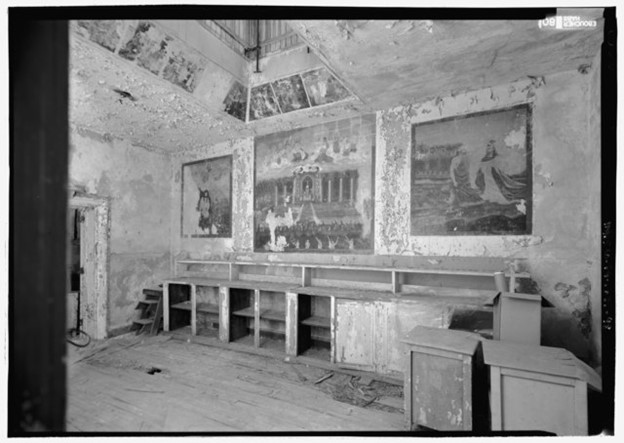

Image 4:

———. Interior View, Chaplain’s Office. HABS PA,51-PHILA,354-. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.pa1207.photos.