Established 2023

How many books in your home were printed using prison labor?

Quite possibly a few. Since about the middle of the nineteenth century until today, incarcerated people have set type, operated printing presses, and bound books inside prisons in North America and around the world. The texts produced through prison labor include dime novels, tax and government forms, newspapers, standardized tests, catalogues for state colleges and universities, envelopes, newsletters, public school report cards, brochures, business cards, and magazines. Many government reports, of the sort sagging shelves in local archives, have been printed using prison labor. There have also been multiple schemes to publish educational textbooks inside prisons, from the primers lithographed in colonial Indian prisons in the 1850s to an 1897 plan by the American Publishers’ Association to print schoolbooks for poor children at Sing Sing. Today, braille textbooks for blind readers are printed inside prisons through the National Prison Braille Network, an initiative of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Quite possibly a few. Since about the middle of the nineteenth century until today, incarcerated people have set type, operated printing presses, and bound books inside prisons in North America and around the world. The texts produced through prison labor include dime novels, tax and government forms, newspapers, standardized tests, catalogues for state colleges and universities, envelopes, newsletters, public school report cards, brochures, business cards, and magazines. Many government reports, of the sort sagging shelves in local archives, have been printed using prison labor. There have also been multiple schemes to publish educational textbooks inside prisons, from the primers lithographed in colonial Indian prisons in the 1850s to an 1897 plan by the American Publishers’ Association to print schoolbooks for poor children at Sing Sing. Today, braille textbooks for blind readers are printed inside prisons through the National Prison Braille Network, an initiative of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Almost none of these texts identify themselves as having been printed by incarcerated people paid nothing or pennies on the dollar, as compared to the cost of a commercial printer.

Because of its entanglement with literacy, printing has long been seen as a noble and respectable activity. This has made it useful to prison administrators who wish to cloak their exploitation of incarcerated labor with lofty rhetoric about the value of education and the dignity of “honest work.”

For a scholarly history of printing presses in prisons, see Whitney Trettien, Prison Labor and the Problem of Print," in the journal Book History, Volume 28, Issue 1 (Spring 2025).

The first person to make this connection was Frederic J. Mouat, a British civil surgeon appointed inspector of prisons in Bengal in 1855. Mouat oversaw an expansion of prison industries in colonial India, including a large workshop of printing presses that he installed at Alipur Central Jail. Incarcerated colonial subjects at Alipur printed many of the thousands of blank forms, government documents, magazines, court proceedings, and book-length reports required to maintain the paper-hungry colonial government.

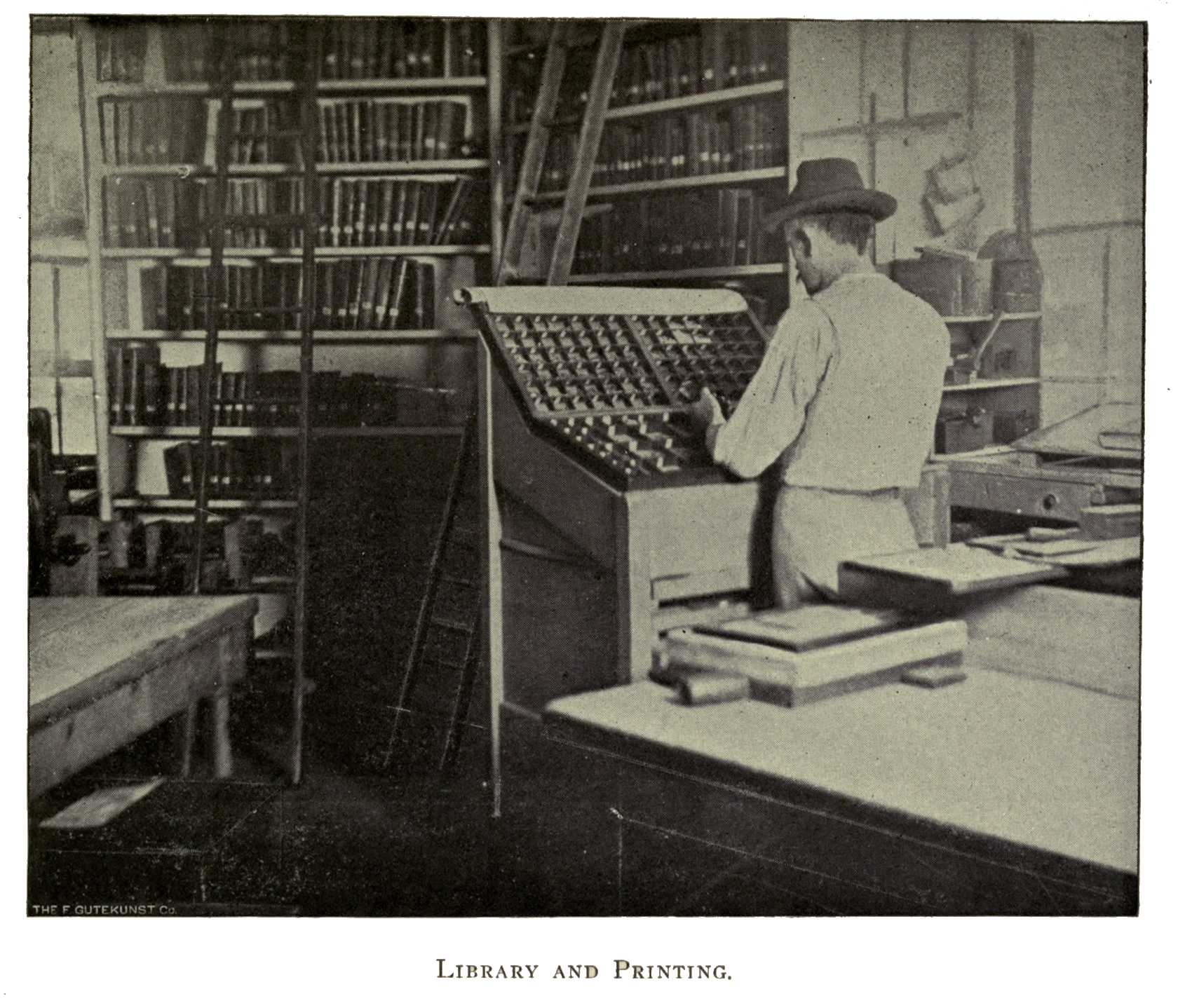

Later, Mouat’s work was taken up by the mid-nineteenth-century British and North American reformers who oversaw the transition from contract labor to the industrial or trade school model of training within prisons. Zebulon Brockway and the Elmira Reformatory were key figures in this shift. In 1883, Brockway purchased a Cottrell cylinder printing press and trained some incarcerated boys on how to operate it. At first, it was only used for internal jobwork; but then a man named Macauly, who had served time at Elmira in 1880, suggested that the school begin printing a prison newspaper. Brockway agreed, and Macaulay organized The Summary, a digest of news printed for internal circulation among those incarcerated at Elmira and seemingly the first publication ever printed, edited, and written by incarcerated people inside a prison. Brockway and Macaulay were the first to bring together the idea of distributing a edifying prison newspaper to incarcerated readers with printing as a noble form of prison labor. It was a winning combination, and the prison newspaper spread quickly across the new reform-minded carceral institutions.

By 1885, the Massachusetts Reformatory at Concord, for criminalized men under thirty, was publishing and printing Our Paper, followed the Prison Mirror at Minnesota State Penitentiary at Stillwater in 1887. By the end of the century, prisons in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Colorado, Ohio, Illinois, Connecticut, Indiana, Iowa, and Missouri also had newspapers. By World War I, the press had spread further south and west to Alabama, Kansas, California, Texas, Georgia, Idaho, Nebraska, Washington, and Wyoming. In these early days, prison newspapers were mainly a means for wardens to broadcast news outside a prison’s walls to those incarcerated within, while sharing news of classes, concerts, lectures, and other events that were becoming part of the new reformatories. However, incarcerated writers soon clamored to be involved, and in fact the third prison paper in the United States, Prison Mirror, was entirely conceived, funded, and produced by incarcerated people. While relatively educated white men were the most prominent contributors and editors, many papers were also printed and published by incarcerated women, girls, and people of color, such as The Booster, a mimeographed newsletter produced at the Virginia Industrial School for Colored Girls in the 1920s and 1930s.

By 1885, the Massachusetts Reformatory at Concord, for criminalized men under thirty, was publishing and printing Our Paper, followed the Prison Mirror at Minnesota State Penitentiary at Stillwater in 1887. By the end of the century, prisons in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Colorado, Ohio, Illinois, Connecticut, Indiana, Iowa, and Missouri also had newspapers. By World War I, the press had spread further south and west to Alabama, Kansas, California, Texas, Georgia, Idaho, Nebraska, Washington, and Wyoming. In these early days, prison newspapers were mainly a means for wardens to broadcast news outside a prison’s walls to those incarcerated within, while sharing news of classes, concerts, lectures, and other events that were becoming part of the new reformatories. However, incarcerated writers soon clamored to be involved, and in fact the third prison paper in the United States, Prison Mirror, was entirely conceived, funded, and produced by incarcerated people. While relatively educated white men were the most prominent contributors and editors, many papers were also printed and published by incarcerated women, girls, and people of color, such as The Booster, a mimeographed newsletter produced at the Virginia Industrial School for Colored Girls in the 1920s and 1930s.

Within twenty years of the first issue of The Summary, there were enough prisons in North America printing newspapers to constitute what has since become known as the penal press: a network of mostly incarcerated editors, writers, poets, and printers exchanging articles, editorials, and news among each other. It flourished in the era of the prison reformatory, when the institution was aimed at changing the personal traits and morals of the incarcerated individual; it continued after the rhetoric around prisons had shifted toward the rehabilitation of the circumstances that had led someone to commit a crime; and it remains a feature of some prison programming today, now alongside podcasts and other broadcast media.

An article on the print shop at Eastern State Penitentiary in a Fall 1966 issue of Eastern Echo, a color magazine written and printed inside the prison but circulated widely outside, shows how advanced some printing operations and their outputs became.

Following a comment on the value of the print shop by Frederick Adams, the magazine shares a series of photos showing linotype, monotype, and intertype machines for typesetting, a small job cylinder press and platen presses, three Miehle verticular presses (a kind of flat-bed cylinder press), a Miehle horizontal press, an MGD 22 offset duplicator, a Multilith 1250-W offset duplicator (used to print the magazine itself), and spaces for imposing, composing, cutting paper, binding books, and shipping materials, all populated with a racially integrated personnel of incarcerated men. It is an impressive printshop that publishes a remarkable magazine, far advanced in both content and technical execution from the crude four-page weeklies printed with movable type in the 1890s. Yet here still the same rhetoric of print’s exceptionalism protects and promotes its place within what had become known by then as “correctional industries.”

Following a comment on the value of the print shop by Frederick Adams, the magazine shares a series of photos showing linotype, monotype, and intertype machines for typesetting, a small job cylinder press and platen presses, three Miehle verticular presses (a kind of flat-bed cylinder press), a Miehle horizontal press, an MGD 22 offset duplicator, a Multilith 1250-W offset duplicator (used to print the magazine itself), and spaces for imposing, composing, cutting paper, binding books, and shipping materials, all populated with a racially integrated personnel of incarcerated men. It is an impressive printshop that publishes a remarkable magazine, far advanced in both content and technical execution from the crude four-page weeklies printed with movable type in the 1890s. Yet here still the same rhetoric of print’s exceptionalism protects and promotes its place within what had become known by then as “correctional industries.”

The story of the American penal press has been written by James McGrath Morris and Russell Baird as part of the long history of American journalism and its censorship.What this narrative has missed is that there likely would be no penal press were it not for the introduction of presswork and typesetting into prisons.

It was precisely the ambiguity of printing as a form of labor both educational to the individual and remunerative to the institution that made it possible for prisons to continue building printshops. And the presence of this ostensibly ennobling work at the heart of “correctional industries” created the conditions necessary for the emergence of penal newspapers and magazines: they were simply a natural extension of the ostensibly edifying bookwork already being done on prison presses. Especially in the early decades of the penal press, wardens often allowed these papers to flourish not in spite of the threat that prison journalism posed to discipline or security, as one might assume, but because they in fact enabled tighter control over an incarcerated person’s time.