Established 2023

Since at least the 1830s, when a wave of reform movements turned public punishment into private penitentiaries, America’s jails and prisons have been laboratories for experimenting with involuntary labor.

Throughout this long history, state officials have justified the exploitation of incarcerated citizens by claiming it offers them marketable skills in trades like cobbling or carpentry. But learning how to repair a shoe or build a chair is different than learning how to print or bind a book. Shoes are simple, salable goods; print is a communication technology. As such, it is both empowering and dangerous: potentially empowering to the individuals who are incarcerated, potentially dangerous to the institutions incarcerating them.

Prison officials knew this. Because they pitched the labor of making texts as a means of rehabilitation, they often had no choice but to support the publishing projects of those incarcerated. But they did so cautiously, “with mixed feelings and some apprehension,” wrote Superintendent Joseph Brierly in an issue of The Eastern Echo. He continued: “My fears were based upon my reasoning that the magazine was a potential tool in the hands of the criminal; a tool to be used by him against society after his arrest and incarceration, such as the jimmy bar, the shiv, and the gun.”

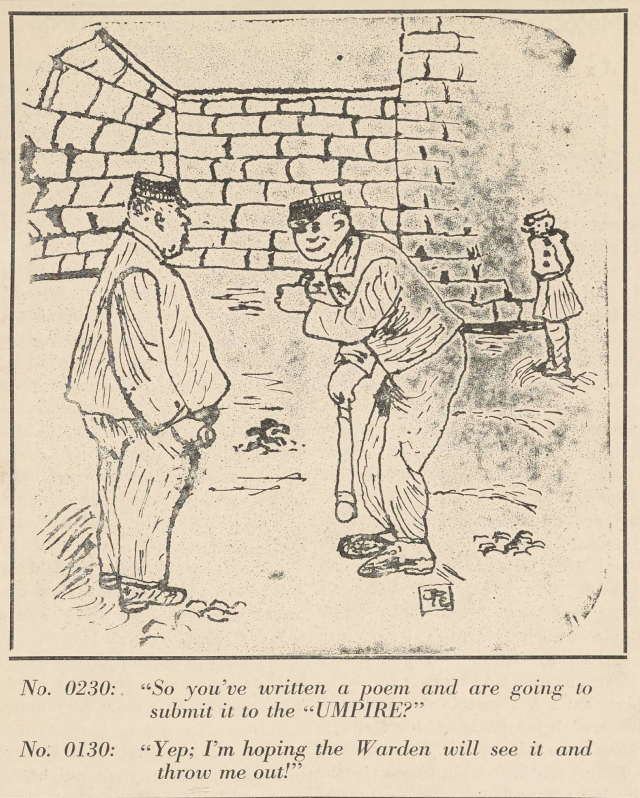

Superintendent Brierly’s fears were warranted. Printed texts are indeed recalcitrant things, their methods of refusal not so easily contained. From the 1890s until the prison’s closure in 1970, the print shop at Eastern State Penitentiary produced many books for the city and state governments, as well brochures and magazines for churches and other non-profit organizations in Philadelphia. When not printing government materials, incarcerated people used these same presses to publish newspapers they wrote and edited themselves, with ambiguous, shifting support from the wardens. The Umpire (ca. 1913-18) appeared first, a newsletter about the prison’s baseball league, including jokes, gossip, and classifieds. Newsletters like Pen Points or Grate-Phil News followed, although most copies are now lost. Finally, an updated and renovated print shops produced The Eastern Echo (1956-67), a full-color magazine for a general readership, which circulated both inside and outside the penitentiary. Each of these periodicals form individual nodes in a vast network of prison publishing that flourished throughout the twentieth century.

The present site focuses on The Umpire, which ran from some time around 1913 to about 1919. To learn more about this newletter, please explore the exhibits below.

What is The Umpire?

Running from 1913 to 1919, The Umpire offers an unparalleled glimpse into the life of the men (as well as some women and children) incarcerated at Eastern State in the early twentieth century. In this exhibit, learn what it looks like, how it was made, and how it survives today.

This exhibit is still under construction.

Nearly every newsletter or magazine issued from the press room at Eastern State contained poetry. There is poetry about the weather and baseball; on aging and advice; on patriotism and war. There are jokes about other incarcerated men. And there is minstrelsy and racism.

Some of the verse is copied from other sources, often newspapers or books in the prison’s library. For instance, William Wordsworth makes an appearance in an issue of The Umpire, extolling the rise of the morning sun. So does children’s author Susan Chauncey Woolsey (pen name Susan Coolidge), on the powers of beginning again.

But by far the most engaging verse is always written by those incarcerated at Eastern State. Click here to learn more about some of the prison’s most prolific twentieth-century poets, or dig into the data yourself using the index of verse.